In 1947, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, visited the Majdanek concentration camp in Poland to support relief efforts after the war.

Just 20 years old, Elisabeth worked in the barracks where children were housed before being sent to death. While sorting shoes on the floor, Elisabeth noticed faint etchings on the walls and realized the children used their fingernails and rocks to carve butterfly images — hundreds if not thousands of butterflies. From that experience, she decided to become a psychiatrist and work with children and the terminally ill.

How, she wondered, could innocent children, condemned to forced labor and death, find a place of beauty in their hearts to draw butterflies....and why?

"The little ones were no longer in cocoons,” Elisabeth remembered. “Now they were butterflies. They would be set free from the hellish concentration camp. No longer prisoners of their bodies. No more torture. No more separation from their mothers and fathers. This is the message they were leaving for me and all those left behind."1

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ groundbreaking inquiry into death and dying was born at that moment. She and her colleagues interviewed thousands of terminally ill patients and uncovered an emotional cycle in the grieving process.

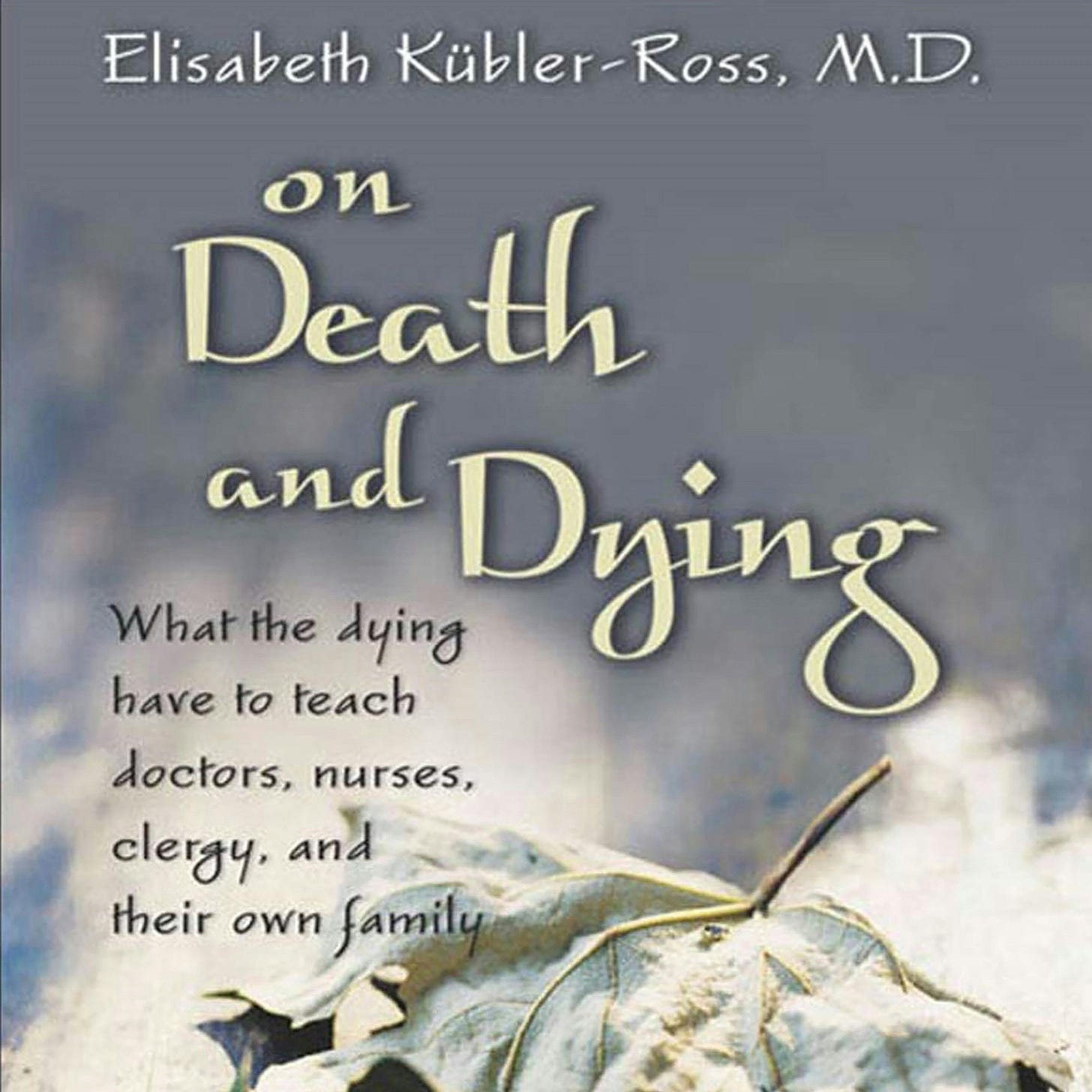

In her landmark 1969 book, On Death and Dying, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross identified five stages of grief:

Denial: "No, not me. It cannot be true."

Anger: "Why me?"

Bargaining: “Can I postpone death with good behavior?"

Depression: “My hopes for a miracle have failed.”

Acceptance: "I submit to the journey; it is out of my hands.”

The Kübler-Ross model for grief took on a life of its own, even becoming a model for corporate change management. By 1974, Kübler-Ross had already regretted its rigidity, writing, “Most of my patients have exhibited two or three stages simultaneously, and these do not always occur in the same order.”

Life does not follow a fixed pattern, but paradoxically, the model caught on for that reason: because it was linear. Kübler-Ross’ model unfolded like a Greek tragedy:

1) No, it can’t be true. 2) Why me? 3) Please, I’ll do better. 4) Sorry, too late, and 6) Accept the inevitable.

In another twist, near the end of Kübler-Ross’ life, in a book co-authored with David Kessler, they added a well-needed sixth stage: meaning.

I didn’t know this history when Hospice Atlanta sent me a thick packet two months after Karen passed. Following my feral instincts, I glanced at the five stages and chucked it in the trash.

“Enough with the pathos!” my yenta instinct bemoaned. Henny Youngman would have agreed: “If the plane starts to dive, grab the stick!”

Ironically, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross discovered this uplift — the butterfly. Those condemned children understood that grief opened a portal, an opening for Good Grief.

The butterfly dances from flower to flower, but first, it has to undergo a dramatic metamorphosis — from caterpillar to cocoon to transformational goo, and finally, it emerges lighter than air.

Having chucked the five stages, I discovered grieving as a form of birthing — something the body instinctively knows to do. Francis Weller, the author of The Wild Edge of Sorrow and grief facilitator, speaks of grief as a movement of energy and a natural process:

“Throughout most of human history, grief has been communal. For example, the Pueblo people of the Southwest have ‘crying songs’ to help move grief along. The Mohawk traditions have a “condolence ritual,” where they tend to the bereaved with an elegant series of gestures, such as wiping tears from the eyes with the soft skin of a fawn. The healers in those traditions know it is not good to carry grief in the body for a long time… In traditional cultures, people were often given at least a year to digest a major loss.

“We have to go into the shadows and bring it out,” Weller continues. “Our hyper-positive tendencies want us to do a spiritual bypass around the mess of it all, but it’s there in that mess that we are most human.”

After 40 years of intimacy under my belt, the floor of my being was yanked away. I hadn’t lived on my own since my twenties, and now I was 70 — an odd time to start from scratch. I didn’t have the luxury of time to wander aimlessly through five stages of loss — I wanted to grab the stick.

Where to begin? In the history of our planet, over 100 billion people have faced loss, so I should be able to find my way. Like Kübler-Ross, my process had five components, but unlike her tragic narrative, I wanted to find my wings for uplift — those butterflies!

ONE - The Soul Journey — “The Universe Didn’t Make a Mistake”

Let’s start with the hardest, especially if you lost a child or a loved one before their time.

“The Universe didn’t make a mistake” implies that the Universe knows what it’s doing. (We hope!) We’re all on a soul journey. This is not magical thinking or belief in a Master Plan. Religious belief has helped people cope with loss across millennia, but belief is not the same as Kübler-Ross’s sixth stage: Meaning.

When a loved one dies, we are stuck holding a pile of pieces — like the pieces in a puzzle box. Imagine a puzzle with no picture on the box! Is this a castle on a hill or a sailboat on the sea?

With a puzzle, you find two blue pieces and assume “sky.” With a loved one, you start with the Soul Journey. They came into this world without a map and traversed childhood, school, career, and accomplishments. Maybe they had a family. One thing led to another, and suddenly, your loved one died. You are stuck with a pile of pieces to find the meaning of their life.

Does your loved one’s story make sense — not the illness — but their time on earth? What was their story about?

Imagine going into a TV writer’s room to study the wall of cards filled with characters, scenes, plot points, and conflict. Follow the cards to see each scene logically — or magically — lead to the next. Can you find a larger mission, a search, a growing, or a knowing? Was it a karmic mission? What were they struggling with, building, seeking, or discovering? A soul journey — despite the pain — is about knowing oneself.

Meaning emerges when you see life’s thematic logic.

Karen’s passing seemed unfitting to her dedicated life. “Why did this lamb of God who loved and supported so many endure such pain and indignity in her final months?”

After Karen passed, I gave a Zoom talk to a large group of friends scattered around the country titled “What does it mean to be healed?” The talk was based on The Invisible Way, a book Reshad Feild wrote about his friend, John Cooke, who died of cancer.

In the final chapter, Reshad wrote:

“Suddenly, John’s body started shaking; ripples passed through every muscle and fiber. I could see he was in great physical pain, yet he was so conscious he was beyond the pain.”

“Using the last of his strength, he moved his head so that he could see through the open window. The blood moved on, a spreading red river. We turned to look with him. The sky turned red in the sunset. The first star shone over the top of the pine tree. The last bird had ceased its calling.

“I love you,” John said. “There is nothing else.”

Forty years earlier, Reshad read from the manuscript, fresh from the typewriter. As I listened, the final line — “I love you, there is nothing else” — left an indelible mark. We were young, in our twenties, and had no real experience with death. And now, seasoned by Karen’s passing, I found Reshad’s semi-fictional account melodramatic. Yet, something about the passage stayed with me all these years.

Later that night, Reshad asked for Alan Hovhaness’ Avak the Healer to be played. We sat closely around Reshad’s chair; he took a sip of gin, leaned forward with piercing intensity, and asked, “Do you understand that John had been healed?”

“Healed?” I thought. “What are you talking about?”

The question, “What does it mean to be healed?” has hovered ever since.

Years later, I understood what Reshad meant — to be healed is not the absence of illness. Healing is the completion of a narrative arc — to be released into Love.

I chanted softly into Karen’s ear as I witnessed the triumphant culmination of her life — to be released into Love. Coming to peace with Karen’s Life, like a coda to a song, helped me embrace the nine years Karen wrangled from the Almighty after her diagnosis. In the writers’ room, I acknowledged the triumph of Karen launching her dream career two weeks after brain surgery.

Ultimately, there is only so much gas in the tank on a soul journey. Karen and I missed the drumbeats signaling the recurrence of cancer, as did her clinicians and radiologists. In the end, the orchestration of events made perfect sense. The Universe didn’t make a mistake.

I went into the writers’ room and saw “Karen Sue,” the young Tennessee girl in her wooded sanctuary, escaping the trauma and abuse of her family life. I saw Sue pack her bicycle onto a plane after college and fly far away — 4500 miles — to begin her nursing career in a Honolulu hospital. I visualized more scenes: her vision quest at age 28 sending her over a Big Sur waterfall on her Saturn Return, the improbability of meeting me a year later, a Jewish guy from Chicago, our marriage as two young Sufis working to bring Rumi to the West, starting a family, moving from LA to Atlanta, her celebrated career, beating-the-odds health journey, and her passing, surrounded family and friends.

I remembered her final words, “Life is so sweet.” The Universe didn’t make a mistake.

TWO — Enter the Portal — “A Major Loss Releases the Energy for Change”

Transformation is a messy business.

Life seemingly comes out of nowhere, but there is a pattern to the shocks in life. In every movie, an inciting incident launches the protagonist on a journey they wouldn’t dream of taking without a shove.

The analogy for these shocks is “dog topples the trash.” You come home from a movie and find chicken bones and take-out boxes splattered across the kitchen floor. “OH MY GOD!” you scream. “BAD DOG! HONEY COME QUICK! GET A BROOM, A MOP!”

The toppled can releases energy. The kitchen fills with action, cursing, and shouting. It’s a big mess, but energy is energy — or, as Reshad said, “Energy is neutral.”

When death topples a lifetime of love, the status quo splits open like a toppled can. The traumatic loss releases life-changing energy — not good energy or bad — but decades-long patterns breaking apart like marital fission. This is a portal, an opening to step through.

Imagine a big wave breaking at the beach.

If you stand knee-deep and oblivious, the wave knocks you over in an explosion of surf, sending saltwater up your nose and sand in your suit.

As the wave hits, you can also:

Dive under the wave and resurface in a quiet sea or

Paddle hard and ride that sucker.

I chose to ride, but it’s not the only choice.

I have a friend who lost her husband to Alzheimer’s. After he passed, she shut the door, dove under the wave, and retreated into silence. She has since sold the house and moved to a retirement community, where she is very happy.

I did the opposite; I rode the wave during my manic month, painting the interior, hosting dinner parties, and writing this book. Each of us enters the portal differently, instinctively knowing the energy for change is a one-time gift.

THREE — The Hereafter is Here — “Karen didn’t go anywhere.”

Those first few nights after Karen passed filled me with terror. One night, I closed my eyes and felt an unexpected intimacy — an energetic presence that was distinctly Karen.

My fears softened when I realized Karen didn’t go anywhere. The hereafter is here.

Her presence was confirmed by reports from all manner of friends and the medical intuitive.

My friend Sarah gave me the book Love is Stronger than Death, a memoir of love after death by Cynthia Bourgeault. Two months after Bourgeault’s spiritual partner Rafe died, Cynthia poked around Rafe’s workshop, feeling forlorn. Suddenly, she felt bubbles of energy tingle through her being. She trekked outside and began to weep.

“As I wept out there in the snow, I began to notice a shift,” she wrote. “Although I was still crying, the emotional sting started to lose force, and a new and tingling presence began to work its way up in me, literally starting from the tips of my toes. I felt like an empty glass slowly being filled with champagne. In spite of myself, I was fascinated. A sparkling, bubbling life seemed to be pouring into me, filling me with such buoyancy that I could no longer sink into despair.”

As I read Bourgeault’s account, one word stood out: Buoyancy. This was the code word Karen and I used nine years earlier at the start of her cancer journey.

We were driving to chemo when I complained about the grueling traffic. Our friend Daniel was at the wheel.

“I just enjoy being together,” Karen beamed as the traffic ground to a halt.

“We shouldn’t have left the freeway for the side streets,” I snarled, but Karen wouldn’t have it.

“I enjoy seeing these neighborhoods where Daniel used to drive his cab.”

At that moment, Karen’s disposition parted the scarlet sea. A magic word appeared that would guide us through the grueling journey ahead. The word was buoyancy — the upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of an immersed object. When they said Jesus walked on water, maybe it was mistranslated Aramaic for buoyancy.

So Karen and I learned to walk on water.

Bourgeault discovered buoyancy as well. She wrote:

“And so here it was: the pure essence of his presence and the immense energy of his love—just as it had always been—only now minus the physical body…

“I see the body of hope as a living, palpable, and conscious energy that holds the visible and invisible worlds together. It is the sap, metaphorically speaking, through which flows the higher communion—the sharing of personal love and the building up and unfolding of the wonders between two people.2

Like Bourgeault, I was painfully alone. Yet, despite the emptiness of the marital bed, it suddenly made sense. We come into this world alone from the sea of love and lose contact with our Source, but rediscover it in life through deep intimacy. Though painful for the survivors, we return to the Source of love.

The Hereafter is here.

I described Karen’s presence to Bhagwan as an enveloping radiance.

“If you think about her, tell stories about her, light candles for her, the radiance is gone,” Bhagwan gently replied. “If you live fully in yourself, you are with her.”

Hmm. Living fully in yourself is the challenge.

FOUR - Take the Torch — “The mission has been passed.”

The surviving spouse is granted unique superpowers. How and why this happens is worth our attention. Consider Yoko Ono:

“When I was about four years old, I had all these ideas,” Yoko shared in an interview. One of these was: “Take one seed from a fruit and another from another, and halve it, put them together, and bury it? It might grow something really strange.”

Yoko asked her childhood friend to write it down. This launched her career as a conceptual artist. “From the beginning, I had decided whenever I get an idea, I have to show it to the world.”

In 1965, Yoko proclaimed, “It’s important to be mischievous.” In her book Grapefruit, she imagined:

“A house constructed of light from prisms, which exists in accordance with the changes in the day.”

After she met John Lennon, he asked her to build a “Light House” in his garden. Yoko explained it was purely conceptual but added, “I don’t know how to do it, but I’m convinced that one day, it could be built.”

After John was murdered in 1980, Yoko committed her life to their shared quest for world peace. Her vision became a reality twenty-seven years later as Imagine Peace Tower on a small island in Iceland.

Four years in the making, the artwork consists of a 4,000-meter-tall beam of light projected from 15 searchlights into prism mirrors and powered by geothermal. The column of lights pierces the cloud cover from a crystal stone monument with “Imagine Peace” carved into 24 different languages.

“This is an answered prayer,” Yoko said. “It reminds one how brief life can be. My love for you is forever.”

When your loved one passes, the sum of their life is imparted as a prayer. The torch is passed to carry it in your remaining life.

"Sleep is hard," Congresswoman Debbie Dingell wrote in 2019.

Dingell described her grief after her husband John Dingell, a Democrat, died at age 92 after battling prostate cancer. A revered member of Congress from Michigan, Dingell was the nation’s longest-serving Congressman — 59 years in office.

"I am wearing one of John’s Michigan sweatshirts, holding another, and letting the memories flood me,” Debbie Dingell shared after his death. “I was so blessed to have this incredible love affair for so many years."

Four years earlier, her husband passed the torch: “I want Debbie to be able to do the things that she wants, and if she wants to run for Congress, I want her to do that.”

After her election, the new Congresswoman, Debbie Dingell, said: We were a team in every sense of the word. We’re still a team. I know his spirit is in me. I have a new normal and I’m working into that new normal.”

In 1989, while waiting to take the stage to give a speech at Stanford, Steve Jobs noticed a beautiful girl sitting next to him.

They started chatting.

Twenty-two years later, Jobs died from pancreatic cancer. And that beautiful girl, who became Laurene Powell Jobs, inherited the Steven P. Jobs Trust. After his death, Laurene Jobs spent several years out of public view — until the moment she took the torch.

Rather than sit on $20 billion, Powell Jobs used it to push for the Dream Act, providing legal status to immigrants who arrived in the U.S. as children. She also supported a long list of other humanitarian causes, the Atlantic magazine, a documentary film, and sports teams.

The New York Times reported on her work with immigrant students:

Marlene Castro knew the tall blond woman only as Laurene, her mentor. They met every few weeks in a rough Silicon Valley neighborhood the year that Ms. Castro was applying to college… Castro became the first person in her family to graduate from college. It was only later, when she was a freshman at the University of California, Berkeley, that Ms. Castro realized that Laurene was the wife of Apple’s co-founder, Steven P. Jobs.

“Her life was about her family and Steve,” world health philanthropist Larry Brilliant said, “but she is now emerging as a potent force on the world stage, and this is only the beginning.”

Laurene Powell Jobs told the New York Times:

“In the broadest sense, we want to use our knowledge and our network and our relationships to try to effect the greatest amount of good. I am so motivated by the stories of the Dreamer students and their families, and I don’t give up because they don’t give up.”

Powell Jobs described the passing of the torch:

“I inherited my wealth from my husband, who didn’t care about the accumulation of wealth,” she said. “I am doing this in honor of his work, and I’ve dedicated my life to doing the very best I can to distribute it effectively in ways that lift individuals and communities in a sustainable way.”

Alexei Navalny was, and still is, Russia's most effective and inspiring opposition figure.

Putin started arresting Alexei Navalny in 2011 and never stopped. The state tried to blind him with chemical attacks, including a nerve agent that put him into a three-week coma. Soon after, he was imprisoned.

“I knew from the outset that I would be imprisoned for life,” Navalny wrote in his diary. “I will spend the rest of my life in prison and die here.”

In 2024, they killed Navalny in prison. Still unsatisfied, the state put out an arrest warrant for his wife, now in exile. Yulia Navalny took up the torch and compiled his prison diaries into the best-selling Patriot — “to use his voice to bring the truth.”

“It’s very important for me to keep his legacy alive,” she told the New York Times from a secure European location. “When you lose somebody very close to you, you want everyone to remember him. Everything changed in his mind after his poisoning because he realized life could end the next day.”

Yulia feels responsible for carrying on her husband’s work despite the danger it puts her in.

“I want our country to be different,” she said. “I want to do it for all the people who are against this regime, and I want to do it for our children, who want to live in Russia, and of course, I want to do it for Aleksei’s memory.

“I want people to know my husband — that he was a great man — but also that he was very kind, very funny, and very beloved. The main problem now is that we supported each other. I am doing all these interviews and meetings, but I wish I could come home and discuss it with him. We could lay in bed, just touching hands. I miss that a lot.”

Karen didn’t leave me a billion dollars.

But like Yulia, I am writing our story.

And unlike Jobs, my income was cut in half the day she died. Suddenly (and quickly), I had to reinvent myself — the focus of this book. There was no inheritance, but she did pass a torch.

I shape-shifted into a new role — taking on Karen’s job in the love business, which meant loving people unconditionally. We joked that she ran the “front of the house” — the maître d' who showered love as guests entered the door — while I ran the “back of the house” — the executive chef who gets the food out on time.

As maître d'amour, Karen was the master at maintaining Bondo — the capacity to form intimate relationships. She maintained these relationships by what we called “spinning the love plates” — like the performer on the Ed Sullivan Show who darted back and forth, spinning wobbly plates each time they needed some love.

This was a new job for the executive chef. The front and back of the house still function as a team — even after the torch was passed.

Debbie Dingell said her marriage was “a team in every sense of the word. We’re still a team. I know his spirit is in me.”

Cynthia Bourgeault described the torch as “a body of hope… a living, palpable, and conscious energy that holds the visible and invisible worlds together.”

Yulia Navalny has mustered immense courage to carry a torch for the children of Russia.

Knowing that you were handed the torch brings meaning to a grief journey. The physical torch comes in the form of inheritance. The timeless torch — the body of hope — fills a grieving heart.

FIVE - Spread Your Wings — “Don’t Let the Grief Plumbing Back Up”

The Grief Advisory Board guffawed when I invoked plumbing for the finale, Number Five, but if you’re a guy, there’s a tool for everything.

During Karen’s stay in the hospital, I faced a flood of test results, doctors, decisions, and feelings. Next came people flying in, hospice, morphine around the clock, funeral arrangements, food platters, and streams of awkward condolences. Preventing an emotional back-flow required flushing the lines minute by minute.

Walking, talking, cooking, and cleaning kept the grief pain manageable. I likened it to those pain charts where the nurse asked, “How’s your pain level today?” You want to keep your grief level between four and six:

This means staying in touch with grief, feeling it, working through it — but not being overwhelmed.

The challenge is to avoid falling into thoughts of expectation. Will she live? How will I survive? Can I handle being alone? Thinking about yourself is expectation — what Rumi called “The Red Death.”

Reshad described the insidious nature of expectation:

There’s a saying… Expectation is the Red Death. Most of us were raised in expectation. We’re expected to be doing something. That expectation sets a pattern for our lives. The red death of expectation is what stifles a human being.”

One trap is looking for results, saying, “If I do this, the result will be good; and if I do not do this, the result will be bad.” These are expectations, “the red death.” Even healing can be a trap.

Suppose a course of treatment is given and something happens. Another treatment is then given and soon a state of perpetual expectation develops. It just goes on and on. The present moment is never faced.

If one has knowledge, one does not expect. I don’t know what will happen in the next moment, so I don’t expect anything. The word expect is very important to look at.

I used to be a racing car driver, and when I was racing, I couldn’t expect the motor to fail; I couldn’t expect the car to crash. All I could do was train my body to steer the car around the track. That’s life.3

As I careened from one exigency to another, I trained my body to stay engaged. If the universe didn’t make a mistake, my job was to remain present. Rather than texting, I picked up the phone. By describing my ordeal one-on-one, I could let my emotional plumbing flow. Even calling wasn’t enough, so I opened the floodgates by writing a blog. When you write, you own your story; you find meaning. The drama ran through me rather than burying me.

Karen once described how she navigated a serious diagnosis by facing her circumstances head-on:

“When you engage something with intention,” Karen explained, “like facing this diagnosis head-on, there’s meaning in the experience. It’s a chicken and egg because when you engage, the meaning develops. I don’t know which comes first, but intention and meaning are connected.”

Three months ago, Karen was calling from the bedroom, “Bruce, come to bed. I need my rubbies.”

And now, I’m engaging grief like a wave head-on. It’s painful, sure, but there’s meaning in the experience — or, as Karen put it, “the meaning develops.”

Engaging changes your sense of time like a child engaging with every caterpillar on every leaf during the endlessness of summer. This was Karen’s secret to “actively engaging grief.”

Those children etching butterflies knew this secret as well. You enter the portal when pay attention to your experience. Maybe a butterfly will emerge.

Bourgeault, Cynthia. Love is Stronger than Death: The Mystical Union of Two Souls (pp. 70-72). Monkfish Book Publishing. Kindle Edition.

![Plate and bowl spinner Eric Brenn performs on an episode of 'the Ed Sullivan Show' called 'the Annual Army Talent Show,' filmed on June 27, 1959. USA. [612 × 608] : r/HistoryPorn Plate and bowl spinner Eric Brenn performs on an episode of 'the Ed Sullivan Show' called 'the Annual Army Talent Show,' filmed on June 27, 1959. USA. [612 × 608] : r/HistoryPorn](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!_2pT!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa6d7520d-ba1d-4104-bdf1-c68d7465cda8_612x407.jpeg)