Failure

Life is a karmic engine. Each failed piston stroke sets you up for another try at creation.

As we watch the wheels fall off the United States as the “shining beacon on the hill,” I want to discuss the meaning of failure.

When I was a kid in college, my dad sold his share of Sherwood Electronics, a pioneering company in the emerging world of high-fidelity. Without much consultation with the family, my dad purchased a car wash in Torrance, California — a wet and clangy mechanical underworld where fancy cars got damaged by tow chains, customers complained, and guys off the street performed wipe-downs for tips.

My dad, Ed Miller, wanted to leave Chicago for sunny California, where he could garden year-round.

That summer, my brothers and I drove the family station wagon from Chicago across the Mojave Desert to meet the family car wash.

“Hi, Dad, we made it,” I announced. “Wow…this is something.”

“Can you vacuum?” my dad asked.

So, we got to work. During dinner that night at a local Denny’s, I sensed something was wrong. My ashen dad stared into an unseen void. I was too frightened and ill-equipped to handle the dark side of my dad’s emotional moon, so I froze, too — we all did.

It became clear that my dad’s car wash venture was a total abject failure.

My dad never recovered financially. Even worse, I managed to inherit my dad’s and his dad’s transgenerational trauma around failure.

Somebody will be quick to point out that I have so much to be grateful for, but that misses the point. Failure forms the centerpiece of our life journeys.

My first encounter with failure as the downstroke in life’s karmic engine came from my Sufi teacher, Reshad Feild.

It was late one night, 1978, Boulder, Colorado, as we gathered around Reshad. Alan Hovhanes played in the background as Reshad took a sip from his gin and tonic.

“When I was a little child, there was no sense of succeeding or failing,” Reshad said. “My God was my parents; I had no sense of wanting or not wanting. The very idea of success or failure did not exist. I wish to speak to you about failure.”

I was 27 years old and ready to launch into my adult aspirations. The last thing I wanted to hear was Reshad talk about failure. His words were unnerving back then, but illuminating for me now. He continued:

“The greatest apparent failure of all time, the most total absolute failure, was Jesus Christ. And yet, his life has become the greatest triumph the world has ever known.

If we look at the work with which I have been involved over the years, we will see an extraordinary failure, apparently. Thousands of people came; communities were born and died. Nothing has lived. Nothing can be seen in our world that is an exemplar of this person’s life's work. And yet, what is failure?

It is said in the Zoroastrian tradition that sooner or later, every human being will be brought to his knees. Thus, we can see failure as a wonderfully creative state,

Because I'm too arrogant to get on my knees and pray unless I realize I am a failure, the world at this time has almost no failure, and therefore, very little creativity.”

Okay, stop right there. No failure, therefore, no creativity? Reshad went on:

“The beginning of creativity lies in the realization that both success and failure are only comparisons. We need to fail every day from any concept that we are succeeding. Then we are brought upon our knees, and the word "failure" becomes creation itself.”

As a “creative” person, you can imagine my confusion. I was geeked up to build that shining city on the hill, to make films, write books, build a business, get married, and raise a family. And here was Reshad, plumbing his emotional depths to pour an elixir from his crushed life. If there was a message, I wanted to avoid his sort of failure at all costs. Next, we got to the main lesson:

“Creation is possible when we have failed totally in this world. Failure is not dependent upon being rich or poor or being in this "this situation" as opposed to "that situation", but failed from the state in which we thought we could exist separate from the whole. That is failure – and that is potentially creation.

Creation is continuously existing, never began, and will never end. A Sufi or a gnostic – a label-less person, preferably – is continuously part of creation.

In creation, there is no failure and there is no success. And yet, he or she comes to that point where apparently there is nothing but failure.

That is why it was stated by Farīd al-Dīn ʿAṭṭār that a dervish is not necessarily responsible for his actions. It is only when there is failure, in one sense, that we can go on.

What does it mean to go on? Obviously, I cannot answer that because each individual will go on as he or she goes on.”

Okay, Reshad, you lost me back then. But now, from my perch of a lived life, I get it.

How the piston stroke of failure works:

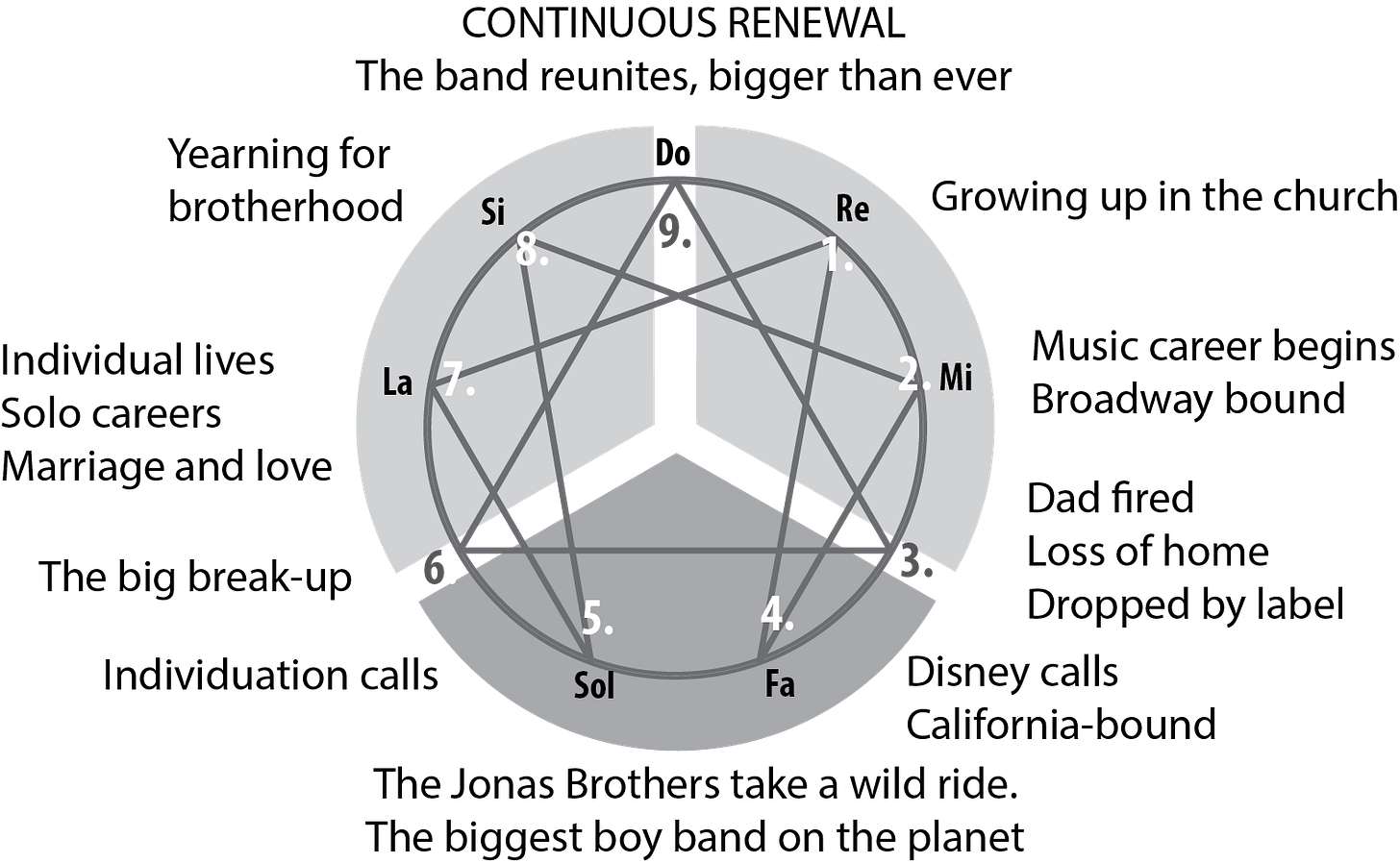

If you place the career of the boy band, The Jonas Brothers on the original enneagram, the push-pull piston of success-failure-success emerges:

The Jonas Brothers grew up singing/performing in a NJ church where their dad was the pastor.

Their young talent brought them to perform in kids’ roles on Broadway. They became a young rock band performing in schools. They were signed by a label.

Performing the “Devil’s music” did not sit well with the parishioners. The church fired their dad, they lost their church provided home and friends, and the family of six was forced into a two-bedroom home, three boys in one room. Mom and Dad argued all day. The brothers retreated to the basement, where they wrote songs. These were dark times. Mom and Dad divorced.

Disney calls with a recording and TV deal. The TV exposure catapults them into sudden international stardom, filling stadiums.

It becomes too much. The Brothers yearn to find themselves individually.

The band breaks up, canceling twenty-three tour dates. Lots of hurt and recrimination.

They get married, raise families, and build solo careers.

After some years, the pain of separation becomes too great. They yearn for their lost brotherhood.

The brothers let go of the hurt and found their way back together, roaring back in with a number-one hit, a multi-city tour, TV performances, and a film.

Let me switch to my hero, Norman Lear.

Lear produced a string of hits in the 1970s and continued to produce throughout his long life. “Over and Next!” was his advice for a life well lived. He urged:

“When something is over, it is over, and we are on to the next. Between those words, we live in moments – make the most of them.” ~ Norman Lear

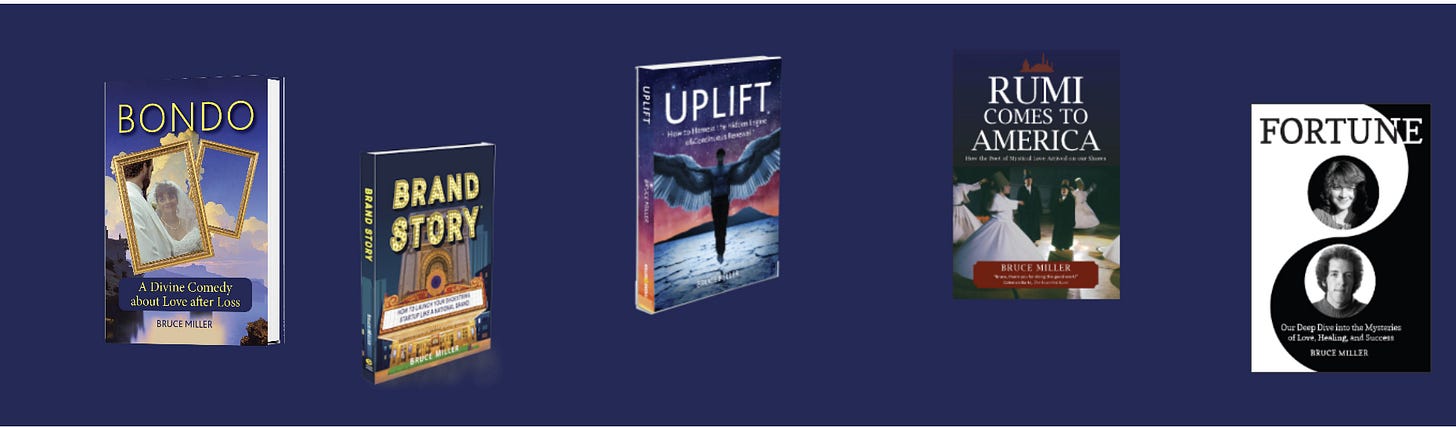

I spent the last ten years pouring every ounce of creative energy into writing and publishing five books, each exploring a different facet of my life journey:

- Fortune – “When major life shocks flip the trajectory of our lives, are these traumatic events random bad luck or part of God’s plan?”

- Rumi Comes to America – “Like a modern-day Forrest Gump, how did a Jewish kid from the suburbs get plucked by the Universe to help launch Rumi, a 13th-century teacher of Islamic jurisprudence, to the West.”

- Brand Story – “After a lifetime of work building successful brands for major companies, can the secret sauce be applied to shoestring start-ups?”

- Uplift – “Can a septuagenarian who exhibits the same physical/mental vitality he experienced in his forties, explain the hidden engine of continuous renewal to a wider world?”

- BONDO – “Is it possible to actively engage grief and find love after a profound loss?”

Each of these books was an absolute, abject, no-holds-barred commercial failure.

Taken together, they drained ten years of my creative resources into a financial sinkhole with nothing tangible to show for the effort. And this Substack has certainly been a failure.

And perversely, from a Jungian integration point of view, the mission has been a triumphant success. But that’s a discussion for another day.

Back to Reshad:

I got up to flip the Hovhanes record. People were nodding off. Someone brought a fresh drink. Reshad continued:

“I have resigned as a teacher because I want the word “teacher” out of it. I can’t teach you something that is impossible to teach, impossible to talk about, and yet goes on. And that is you, and that is me. And that is what is going on… you cannot teach this.

Yes, I can teach some of the greatest gifts I’ve been given, but I cannot be a teacher anymore because I know the meaning of failure. Not as a negative state, nor as the opposite to success, but as the realization that each one of us must confront sooner or later in our lives.

Failure is not a guilty state of life. It is the realization that we are powerless in the face of God. I pray that you will help me in the rest of my life, and I will most certainly help you to come to that point in which there's nothing left to do but to serve.”

Put some of that in your coffee.

When people ask me, “How are you doing?” I borrow the line from SNL’s Cecily Strong impersonating Fox’s Jeanne Pirro, aka “Judge Box of Wine,” aka Trump’s DC District Attorney.

“I’m still here,” is my stock reply.

This is also my take on Reshad’s line, “And that is you, and that is me. And that is what is going on… you cannot teach this.”

I’m still here. Thanks to Norman Lear, I have embarked on another book – A NOVEL! (Someone slap me.) Technically, a “roman de clef” – a memoir disguised as a novel. My next book, “Sid & Sue: An Alchemical Marriage,” will jettison all the philosophy and dramatize the juicy marital bits.

Norman Lear wrote his memoir at age 92 and launched a podcast at age 95. He died a couple of years ago at age 101.

So, friends, despite our ongoing train wreck of failures, we are not washed up yet.

I appreciate your perspective and the lines of Reshad and others. I think Elizabeth Gilbert advised never to try and make a living from your creative passion. I really like your style of writing/speaking, and the content definitely speaks to me - perhaps a shared history? Nevertheless, good writing luck with the novel and I would contribute a slap.... Cheers

Thanks, Bruce; sharing with Bisan Owda - God knows she needs it.