While poking in a closet at the budding age of 13, I found an old 16 mm film camera — the one used by my parents to capture my babyhood. I studied the shutter, sprockets, and pull-down claw like a mechanical talisman. With my newfound Excalibur in hand, I sensed the power to warp the physical universe. A theophanic thought entered my brain: shoot with the camera upside down, then rewind the footage end to front to project normal life backwards. No big deal in the digital world, but in the analog age, seeing Rob purge beautifully formed spaghetti onto his fork distorted space and time in a way Einstein couldn’t touch.

By high school, I became a budding film wunderkind.

I presented films on the coffee house circuit and as part of our high school musicals. For Bye Bye Birdie, I scripted our Elvis character to step out of a Boeing 707, then chased by a crowd of screaming fans out of the jetway, through the concourse, down the escalator, and out the terminal. Back then, you could innocently stroll into the cabin of an emptied American Airlines plane at the gate, frame the shot, and call, “Action!”

During my high school senior year, I studied experimental films at DePaul University,

The seminar was hosted by my boyhood hero, a young Roger Ebert. Roger had been hired as a freelancer to write fluff for the Chicago Sun-Times Sunday magazine. When the paper’s lone film critic retired, the 24-year-old Ebert became Chicago’s full-time movie critic.

In 1969, film was undergoing a creative revolution, and here I was, a skinny high school kid, watching and listening to the pioneers at cinema’s edge — the Kuchar brothers, Robert Nelson, Bruce Conner, and Stan Brakhage — film artists pushing the boundaries of what “movies” can do or even be. Brakhage took film stock, painted it, burnt it, and even glued translucent moth wings to it. The older folks didn’t know what to do with ten minutes of epileptic flicker, but I settled into a deep connection with Brakhage’s vision — a meditation on the luminescence of consciousness itself. Brakhage’s 1959 film, “Window Water Baby Moving,” photographed his wife in childbirth as an orgiastic swirl of pleasure, pain, exhaustion, and exaltation. Watch it on YouTube.

By college, my camera was primed to capture the pent-up angst inside the classroom and find its ecstatic release in nature.

My esoteric romp, Monsieur Gardei, about a student fleeing the shackles of his mind, won the University of Illinois Film Festival and became my ticket to UCLA film school.

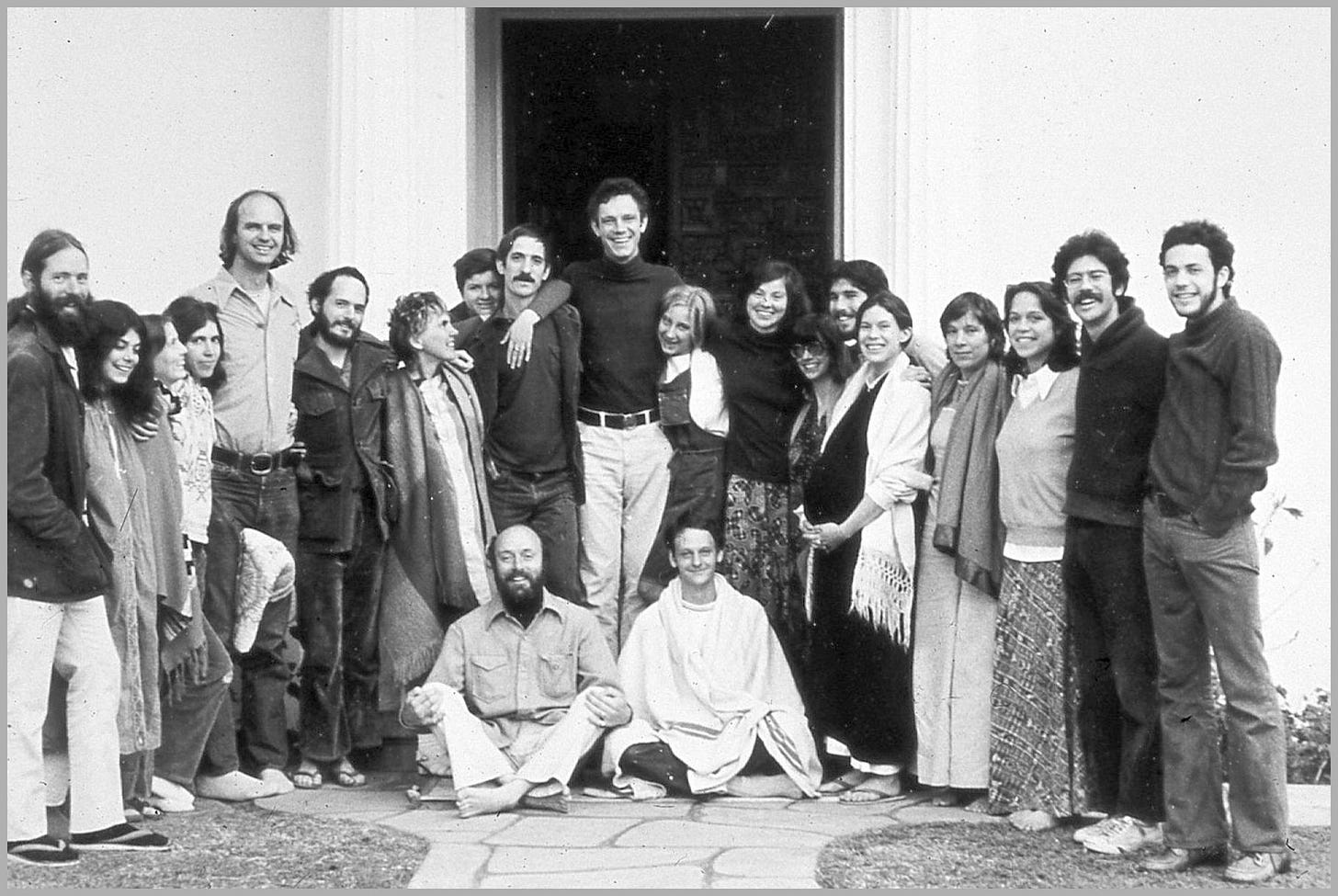

I was already deeply immersed in the leading edge of experimental cinema by the time I entered UCLA. For my Project One, I set my camera on freeway overpasses, downtown buildings, and up and down the Big Sur coast to create Inner Nature.

For the scene of the camera zooming up the stream, I strung a cable between two trees over the stream, hung the camera upside down on pulley wheels like a zip line, and instructed my helper to release the camera and dive out of the frame. The camera is gliding downstream, but because the camera is upside down, I reversed the film end-to-end to glide upstream.

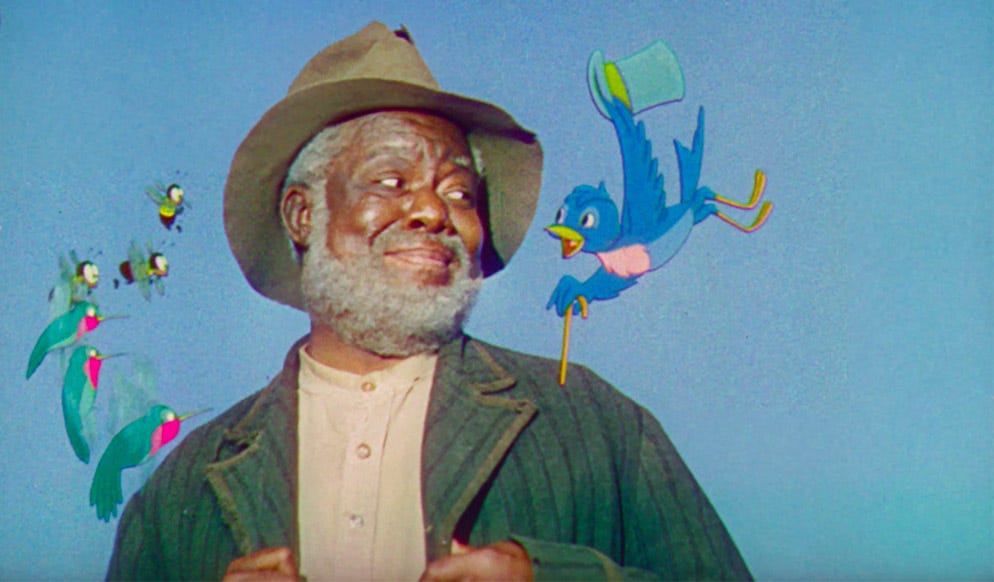

The shot of streaks in the sky used rudimentary bipack printing — a technique Disney used to combine live action and animation (example: the bluebird on his shoulder in Song of the South.

The steps I took to create this effect in my garage are crazy-making to describe, and it “almost” worked.

And for you young un’s, the film was edited with a razor blade, splicing tape, a viewer, hand-cranked reels, a bin filled with shots, and pieces of sound on 16 mm mag film. The edited film was taken to a film lab that inserted the dissolves and married the audio.

Since I find a way in every post to share “too much information,” Pat, the young art student meditating on the downtown bus bench and in the hills of Malibu, also relieved me of my virginity.

My film, Inner Nature, won the Jim Morrison Award for best Project One (Jim Morrison was a UCLA film student before he said, “screw this” and started a band). In the spirit of random association, there is a “break on through to the other side” link in my brain between Jim Morrison and the aforementioned Pat.

My film was also chosen for the Academy Awards Student Film tour. For the transfer, I recently did a “garbage scan" — turning on the projector and aiming the video camera at the wall. I apologize for the fuzziness, plus 50 years of washed-out color. I recreated the soundtrack with new audio.

I want to acknowledge the breakthrough work of classmate Louie Schwartzberg. He was ahead of me, getting his master’s degree, but we were the only two following this particular creative impulse. I can’t overstate how ahead of our time Louie and I were.

Schwartzberg pioneered time-lapse photography of the natural world and has produced four decades of commercial work in numerous commercials. His current film, Fantastic Funghi, is mindblowing. I highly recommend watching the behind-the-scenes video more than the movie:

Louie Schwartzberg: How Mushroom Time-Lapses Are Filmed

Over the decades, I have vacillated through cycles of angst from trading my film career for a lifetime of consciousness exploration. It wasn’t funghi, but cactus that gave me the fortunate or unfortunate glimpse of what’s behind the curtain of life while I was at UCLA. When I discovered that self-realization WAS the purpose of one’s life, I sold all my film gear.

My first teacher, an old Jewish mystic/rabble-rouser named Mory Berman, whom I encountered then, asked me what I wanted to do with my life. When I answered “film artist” he was shocked and dismayed.

“ARTEEST!? You just end up in the CUCKOO HOUSE!”

And that ended that. The rest is history.

Share this post